Disclaimer: The author of this text is still and eternally non-native English-writer, so please excuse him for his grammar errors, mistypes and stupid bravity without any malice, but please consider correcting his mistakes using his e-mail without any commiseration. (TODO: Remove this portion of text when everything wrong will be fixed).

Are you interested in a functional approach to parsers generation? Well, I’m sure you do, even if, at your side, you’re not sure what it means exactly. It’s just because anything that connects parsers and functional programming in practice can be nothing but joyful… Though, I’ll try to be very short in sentencing (is there a word like this?), to be sure not to bore you, if it ever may happen. Also in near future I’ll provide you with few rather good alternatives to reading this short-sentenced article.

Some links to keep in your background tabs while reading this:

- peg.js-fn repository at github

- peg.js repository at github

- all operators in one gist

- the generated parser example (source, comparison)

- the generated parser example – 2 (source, comparison)

Part 1. Story.

Have you tried to read a parser code, generated with a common parser generator? In most cases it’s an unreadable crap, especially in comparison to parser grammar you composed. Though what happens is actually right – because the generated parser is totally not intended to be readable by human at all, but parse as fast as possible. Even though the parser code may be self-repeatable in a lot of places and may weight much more KBs or even MBs because of this.

In most cases, a generator takes your grammar, walks over the AST, finds some creepy code template for every used operator, generates a lot of variables named in a way like __myParserStackVar257, injects your values into these templates using these variables, and pushes the filled templates inline, one by one, into the resulting file. Sometimes it minifies a code by grouping templates with functions for every rule, or, in better case, uses binary code, which is though, even less readable.

My last study is based on the question: “What if there would be a parser generator which generates the human-readable code, as folded as possible, less aimed to fastest speed but more to smallest size?”. May be there actually is one (or two), but I’m not sure in amount of how functional they are.

It started two years ago, actually I was in need of some specific JS-driven-parser, so I discovered peg.js by David Majda and wrote myself a custom grammar. And a parser, which used this grammar as origin, appeared to have a weight of several MBs (!) in result, in my case – so I though I should definitely try to optimize it. The size, not the speed. Here’s the exact point where the mentioned question appeared in my head. So I rewrote the generating part of peg.js, considering David’s code was quite readable (not the generated one, though – still, the latter one followed the Great Parsers Rule of Non-Readability; and actually there was no binary code support at that point of peg.js development).

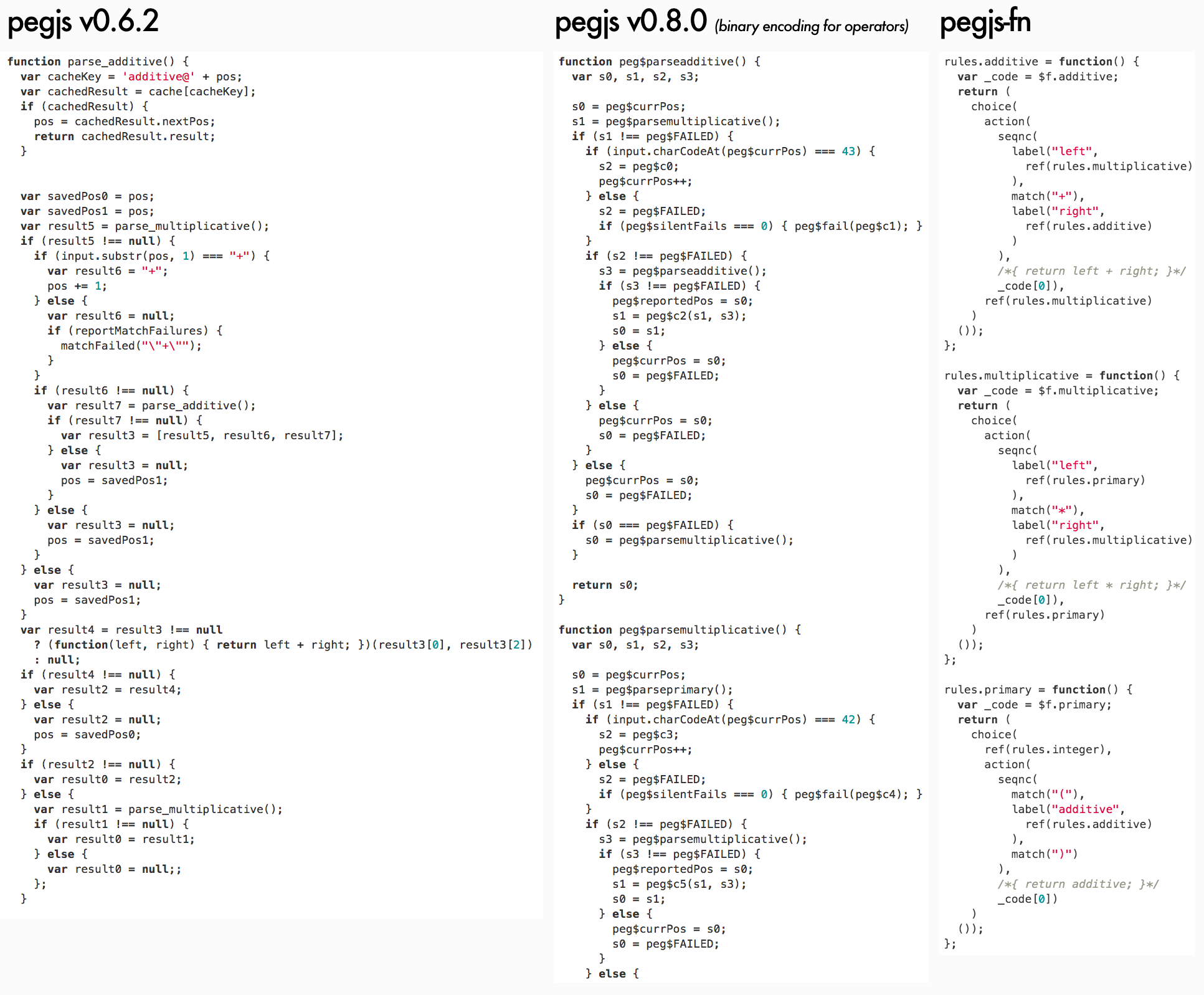

But let’s skip long stories and I’ll show you the resulting code example. And the comparison with the original code and binary code. The source is arithmetics grammar, given below.

You may open this image in new tab (right click → Open in new Tab) to see it in full size.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | /*

* Classic example grammar, which recognizes simple arithmetic expressions like

* "2*(3+4)". The parser generated from this grammar then computes their value.

*/

start

= additive

additive

= left:multiplicative "+" right:additive { return left + right; }

/ multiplicative

multiplicative

= left:primary "*" right:multiplicative { return left * right; }

/ primary

primary

= integer

/ "(" additive:additive ")" { return additive; }

integer "integer"

= digits:[0-9]+ { return parseInt(digits.join(""), 10); }

|

So you see, the one on the right is much much more readable and compact.

Though yeah, this variant of parser is also parses much slower, at least in case of using JavaScript engine for its generation.

I’ve investigated in that, and I actually know that main cause of this speed decrease is in the fact that generated parsers are overwhelmingly exception-driven (yes they do, which means some largely re-used try/catch blocks mentioned later in this article, but actually it doesn’t affects operators or rules code a lot). And it’s a common known performance flaw of JS engines, which may quite easily be solved with hacks or by re-implementing Either monad (thx guys, I missed that one before!) – but using them will break parsers readability just in favor of what single language lacks of, so I won’t do it in this article, since it’s more a theoretical one.

Anyway, if speed is highly important for you, you may safely treat the code below as a pseudocode which will make it language-independent, or replace it with some similar code with your own hands, or may be using another language will just neutralize these speed issues.

What I consider innovative is massive usage of partial function application in generated code and, as it appeared in the end, the overall simplicity and functional beauty of operators' code ‘mini-patterns’. Most part of my life I am truly a modest guy, so please note that I overcome myself to make you pay proper attention to the benefits of the approach). And also, without David’s hard work there’d be no basement for me to build on. No, false comparison. No walls, fundament, finely tuned electricity network, gas tubes system, properly configured and built water system, to put my roof on. That’s closer.

I named it peg.js-fn and all the code is located at github.

Since people will probably ask, I need to mention that, for sure, all of peg.js tests are successfully passed by peg.js-fn.

So the third part of the article is about the structure of generated parser code, in details, on how it works from the inside, and a second one is a just a list of all 18 operators' code snippets with short comments. Just in case I’ll get your interest in internals of the approach.

Part 2. Code. Parsing operators.

The main fuel for parsing process in peg.js-fn is partial function application – this power is achieved with an ability of slightly modified functions to be called twice and to get all of the required arguments saved at first call, and second one just says “please apply the arguments you’ve stored before and call this function NOW, I mean IMMEDIATELY”. Actually, it’s just a sub-case of partial application, so I call this variant with special name, “_postponed functions_” (or “_postponable_”, whatever you like). The way its done is not important for this article, if you really want to know, though, think of Function.bind or take a look at generated parser examples. All the parsers we produce in our Great Parser Factory are powered with this fine-selected fuel. This moves us the fastest way towards both parser readability and execution economy, since it allow us to write, say,

1 | sequence(match('Gand'), choice(match('alf'), match('hi')))

|

without actually performing both matches inside the choice operator – they provide us an option to skip unrequired call of the second match function, when we got 'Gandalf', but not 'Ghandi' as an input string given to our tiny little parser.

This way, the code inside choice operator may look like:

1 2 3 4 5 | function choice(f1, f2) {

return function() {

return f1() || f2();

}

}

|

So JavaScript engine will skip second call if first one returned some value with enough truthful meaning for operator. Both readable and economic, preciousss!!

Following this example you might observe that every operator in generated parsers is a postponed function (at least, but not at last). I’ll list them all below, one by one, all The Mighty 18 of them.

They are intended to impress you at the first glance, so no need in getting everything to the deepest deep – later you’ll have a chance either to dig into any level of details you’ll find required, or freely drop it as useless just after this chapter’s end. [Or you may drop it even here, why bother?]

A quick look into global things:

inputvariable contains text to parse;ilenvariable contains input length;cc()function returns current character in parser position;posvariable contains current parser position;pposvariable contains parser position before execution of current rule, may be forcely overwritten;EOIis just an alias for end of input;failed(expected, found)function throwsMatchFailedexception from the inside, but also fills it with with important information like line number and character number in the souce text where the failure occured;safe(func)callsfunc, but preserves (подавляет)MatchFailedexceptions occured whenfuncwas called, while saving them to error stack;cctxobject holds variables accessible at this nesting level and above (throughprototypechain); details of that will be covered later, if you’ll ever need them.inctx(func)function creates a personal nesting level of context for the provided function, when function will finish its execution, level will be returned back;maame as above, details will be covered below, don’t you worry;

0. example

This example demonstrates the template used in subsections below to describe you the every next operator. You’ll find the short but lyrical description in this place. If you are unfamiliar with PEG syntax while you’re still reading at this point, please undoubtedly follow this link to find out the basics (though it’s a bit customized version we use here, if you need the real world standard – better follow this specification).

- syntax:

PEG syntax for this operator - example:

example of PEG rule, composed using this operator - code:

JS code, as it appears in generated parser for the above rule

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | function example() {

// a code of the operator function, with the postponing

// wrapper omitted, since it's the same in every one of them

// and programmer may wrap all of the operators later him-

// herself this way... and also anyway it is described in

// very details in the next chapter

}

|

1. ch

This operator hoists the next character from the text. If current position is greater than input length, it fails with telling that parser expected any symbol and got end-of-input instead. If next character is what we searched for, input position is advanced by one.

- syntax:

. - example:

start = . . . - code:

rules.start = seqnc(ch(), ch(), ch());

1 2 3 4 | function ch() {

if (pos >= ilen) failed(ANY, EOI);

return input[pos++];

}

|

2. match

This operator tries to match next portion of an input with given string, using string length to consider the size of a portion to test. If the match passed, input position is advanced by the very same value. If input position plus string length exceeds input length – parser fails saying it reached end-of-input. If input does not contains the given string, parser fails saying current character and expected string. (It is possible to provide which part of input exactly was different, but original peg.js tests do not cover it and it’s commonly considered optional, so it may be a homework for a reader).

- syntax:

"<string>",'<string>' - example:

start = . 'oo' - code:

rules.start = seqnc(any(), match('oo'));

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | function match(str) {

var slen = str.length;

if ((pos + slen) > ilen) { failed(str, EOI); }

if (input.substr(pos, slen) === str) {

pos += slen; return str;

}

failed(str, cc());

}

|

3. re

This operator tries to match using symbols-driven regular expression (the only allowed in peg.js). The regular expression may have some description provided, then this description will be used to describe a failure. On the other branches, this operator logic is similar to the one before.

- syntax:

[<symbols>],[^<symbols>],[<symbol_1>-<symbol_n>],[^<symbol_1>-<symbol_n>],"<string>"i,'<string>'i - example:

start = [^f-o]+ - code:

rules.start = some(re(/[^f-o]/));

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | function re(rx, desc) {

var res, desc = desc || rx.source;

if (res = rx.exec(input.substr(pos))) {

if (res.index !== 0) failed(desc, cc());

pos += res[0].length; return res[0];

} else failed(desc, cc());

}

|

4. text

text operator executes the other operator inside as normally, but always returns the matched portion of input text instead of what the inner operator decided to return. If there will be failures during the inner operator parsing process, return code will not ever be reached.

- syntax:

$<expression> - example:

start = $(. . .) - code:

rules.start = text(seqnc(ch(), ch(), ch()));

1 2 3 4 | function text(f) {

var ppos = pos;

f(); return input.substr(ppos, pos-ppos);

}

|

5. maybe

This operator ensures that some other operator at least tried to be executed, but absorbs the failure if it happened. In other words, it makes other operator optional. safe function is the internal function to absorb operator failures and execute some callback if failure happened.

- syntax:

<expression>? - example:

start = 'f'? (. .)? - code:

rules.start = seqnc(maybe(match('f')),maybe(seqnc(ch(), ch())));

1 2 3 4 5 6 | function maybe(f) {

var missed = 0,

res = safe(f, function() { missed = 1; });

if (missed) return '';

return res;

}

|

6. some

This operator executes other operator the most possible number of times (but at least one) until it fails (without failing the parser). If it failed at the moment of a first call – then the whole parser failed. If same operator failed during any of the next calls, failure is absorbed without advancing parsing position further. This logic is often called “one or more” and works the same way in regular expressions. In our case, we achieve the effect by calling the operator itself normally and then combining it with immediately-calledany (“zero or more”) operator described just below.

some operator returns the array of matches on success, with at least one element inside.

- syntax:

<expression>+ - example:

start = 'f'? .+ - code:

rules.start = seqnc(maybe(match('f')), some(ch()));

1 2 3 | function some(f) {

return [f()].concat(any(f)());

}

|

7. any

This operator executes other operator the most possible number of times, but even no matches at all will suffice as no failure. any operator also returns an array of matches, but the empty one if no matches succeeded.

- syntax:

<expression>* - example:

start = 'f'+ 'o'* - code:

rules.start = seqnc(some(match('f')), any(match('o')));

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | function any(f) {

var s = [],

missed = 0,

on_miss = function() { missed = 1; }

while (!missed) {

s.push(safe(f, on_miss));

}

if (missed) s.splice(-1);

return s;

}

|

8. and

and operator executes other operator almost normally, but returns an empty string if it matched and failures expecting end-of-input if it failed. Also, everything happens without advancing the parser position. pos variable here is global parser position and it is rolled back after the execution of inner operator. nr flag is ‘no-report’ flag, it is used to skip storing parsing errors data (like their postions), or else they all stored in order of appearance, even if they don’t lead to global parsing failure.

It’s important to say here that, honestly speaking, yes, peg.js-fn is aldo driven by exceptions, among with postponed function. One special class of exception, named MatchFailed. It is raised on every local parse failure, but sometimes it is absorbed by operators wrapping it (i.e. safe function contains try {...} catch(MatchFailed) {...} inside), and sometimes their logic tranfers it to the top (global) level which causes the final global parse failure and parsing termination. The latter happens once and only once for every new input/parser execution, of course.

- syntax:

&<expression> - example:

start = &'f' 'foo' - code:

rules.start = seqnc(and(match('f')), match('foo'));

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | function and(f) {

var ppos = pos, missed = 0;

nr = 1; safe(f, function() {

missed = 1;

}); nr = 0;

pos = ppos;

if (missed) failed(EOI, cc());

return '';

}

|

9. not

not operator acts the same way as and operator, but in a bit inverse manner. It also ensures not to advance the position, but returns an empty string when match failed and fails with expecting end-of-input, if match succeeded.

- syntax:

!<expression> - example:

start = !'g' 'foo' - code:

rules.start = seqnc(not(match('g')), match('foo'));

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | function not(f) {

var ppos = pos, missed = 0;

nr = 1; safe(f, function() {

missed = 1;

}); nr = 0;

pos = p_pos;

if (missed) return '';

failed(EOI, cc());

}

|

10. seqnc

This operator executes a sequence of other operators of any kind, and this sequence may have any (but finite) length. If one of the given operators failed during execution, the sequence is interrupted immediately and the exception is thrown. If all operators performed with no errors, an array of their results is returned.

- syntax:

<expression_1> <expression_2> ... - example:

start = . 'oo' 'bar'? - code:

rules.start = seqnc(ch(), match('oo'), maybe(match('bar')));

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | function seqnc(/*f...*/) {

var ppos = pos;

var fs = arguments,

s = [],

on_miss = function(e) {

pos = ppos; throw e; };

for (var fi = 0; fl = fs.length;

fi < fl; fi++) {

s.push(safe(fs[fi], on_miss));

}

return s;

}

|

11. choice

This operator works similarly to pipe (|) operator in regular expressions – it tries to execute the given operators one by one, returning (actually, without advancing) the parsing position back in the end of each iteration. If there was a success when one of these operators was executed, choice immediately exits with the successful result. If all operators failed, choice throws a MatchFailed exception.

- syntax:

<expression_1> / <expression_2> / ... - example:

start = . ('aa' / 'oo' / 'ee') . - code:

rules.start = seqnc(ch(), choice(match('aa'), match('oo'), match('ee')), ch());

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | function choice(/*f...*/) {

var fs = arguments,

missed = 0,

my_e = null,

on_miss = function(e) { my_e = e; missed = 1; };

for (var fi = 0, fl = fs.length;

fi < fl; fi++) {

var res = safe(fs[fi], on_miss);

if (!missed) return res;

missed = 0;

}

throw my_e;

}

|

12. action

In peg.js any rule or sequence may have some javascript code assigned to it, so it will be executed on a successful match event, and in latter case this code has the ability to manipulate the match result it receives and to return the caller something completely different instead.

Commonly the operators which themselves execute some other, inner operators, (and weren’t overriden) return the array containing their result values, if succeeded. Other operators return plain values. With action, both these types of results may be replaced with any crap developer will like.

By the way, the code also receives all the values returned from labelled operators (on the same nesting level and above) as the variables with the names equal to the labels. See more information on labelling below.

- syntax:

<expression> { <javascript-code> } - example:

start = 'fo' (. { return offset(); }) - code:

rules.start = seqnc(match('fo'), action(ch(), function() { return offset(); }));

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | function action(f, code) {

function inctx(function() {

ppos = pos; var res;

f(); res = code(cctx);

if (res === null) { pos = ppos;

failed(SOMETHING, NOTHING); }

return res;

});

}

|

13. pre

The rule in peg.js also may be prefixed/precessed with some JavaScript code which is executed before running all the inner rule operators. This JavaScript code may check some condition(s) and decide, if it’s ever has sense to run this rule, with returning a boolean value. Of course, this code does not advances the parser position.

- syntax:

& { <javascript-code> } - example:

start = &{ return true; } 'foo' - code:

rules.start = seqnc(pre(function() { return true; }), match('foo'));

1 2 3 4 | function pre(code) {

ppos = pos;

return code(cctx) ? '' : failed(cc(), EOI);

}

|

14. xpre

Same as pre operator, but in this case, reversely, false returned says it’s ok to execute the rule this operator precedes.

- syntax:

! { <javascript-code> } - example:

start = !{ return false; } 'foo' - code:

rules.start = seqnc(xpre(function() { return false; }), match('foo'));

1 2 3 4 | function xpre(code) {

ppos = pos;

return code(cctx) ? failed(cc(), EOI) : '';

}

|

15. label

label operator allows to tag some expression with a name, which makes it’s result to be accessible to the JavaScript code through variable having the exact same name. Since you may execute JavaScript code in the end of any sequence operator sqnc by wrapping it with action operator, you may get access to these values from everywhere, and only bothering if current nesting level has access to the label you want to use.

- syntax:

<name>:<expression> - example:

start = a:. 'oo' { return a + 'bb'; } - code:

rules.start = action(seqnc(label('a', ch()), match('oo')), function(a) { return a + 'bb'});

1 2 3 | function label(lbl, f) {

return cctx[lbl] = f();

}

|

16. Rule

This operator is different from others, because it just wraps a rule and calls its first wrapping operator immediately and nothing more. It only used to provide better readibility of parser code, so you (as well as parser itself) may link to any rule using rules.<your_rule> reference.

- syntax:

<rule_name> = <expression> - example:

space = " "foo "three symbols" = . . .start = !space foo !space - code:

rules.space = function() { return (match(' '))(); };rules.foo = function() { return (as('three symbols', seqnc(ch(), ch(), ch())))(); };rules.start = function() { return (seqnc(not(ref(rules.space)), ref(rules.foo), not(ref(rules.space))))(); };

1 2 3 | rules.<rule_name> = function() {

return (<root_operator_code>)();

}

|

17. ref

…And if we plan to call some rule from some operator with rules.<rule_name> reference, we need to make current context accessible from the inside. Context is those variables who accessible at this nesting level and above (nesting level is determined with brackets in grammar). This provided with some complex tricks, but we’ll keep them for those who want to know all the details – if you’re one of them, the next chapter is completely yours.

- syntax:

<rule_name> - example:

fo_rule = 'fo'start = fo_rule 'o' - code:

rules.fo_rule = function() { return (match('fo'))(); };rules.start = function() { return (seqnc(ref(rules.fo_rule), match('o'))(); };

1 | function ref = inctx;

|

18. as

The final operator creates an alias for a rule so it will be referenced with another name in error messages. And it’s the only purpose of this one, the last one.

- syntax:

<rule_name> "<alias>" = <expression> - example:

start "blah" = 'bar' - code:

rules.start = function() { return (as('blah', match('bar')))(); };

1 2 3 4 | function as(name, f) {

alias = name; var res = f();

alias = ''; return res;

}

|

So here you go, the list is finished and I hope you now have the vision of a generated parser code as a LEGO-bricks, all types and kinds listed here. By the way, here’s the Gist with all operators code from above with no meaningless wrapping text: click here. If you want to dig into details and tricks, the next chapter will cover them, but it is completely optional and on your own will.

Details

If you are reading this chapter, then seems you are interested in the deepest secrets of a generated parser. Please remember, that you are totally not ought to! And, to be honest, there are not secrets at all there, just a boring, almost bureaucratic, stuff. So if you accidentally started from this chapter (this article is huge, so I suppose it’s rather easy to get lost here – no panic…), just head to the top and start from the beginning, go straight, and try to reach this very point from different direction – this way you’ll find yourself in much more comfortable situation.

For those who haven’t left us – let’s start.

A generated parser consists of several parts, in given order (later we will inspect each of them separately):

- Global variables, just

input,pos(current parsing position) &p_pos(previous parsing position) are here. And parsingoptions. Four of them, and it’s actually enough. They’re accessible both to user code and parser code; - User code from a parser grammar, wrapped in it’s own closure, so it will only have access to functions defined in this closure and global variables. It has no access to internal parser code, which is itself isolated in another closure. Though we store user code in an object, so parser will have access to it. Oh, if you wonder where from we got this code, it’s the one user may write in grammar prelude, inside

actions and forpreandxpreoperator; - Parser closure, which, in its turn, consists of:

- Rules, those ones, which were defined in a parser grammar and were converted to javascript code, same way as in examples for operators above, like

rules.space = function() { return (match(' '))(); };; - Operators code, presented exactly as above, but, of course, there are only the ones included, that were used in the rules above, at least once;

- Internal parser variables, Context management functions;

parse()function, the only one exported to user;MatchFailed,SyntaxErrorexceptions definition, parse error handling code;

- Rules, those ones, which were defined in a parser grammar and were converted to javascript code, same way as in examples for operators above, like

- A call of the parser closure defined above, to prepare its variables only once for several parsing sessions.

Here’s the gist with the complete code of a parser generated using some simple grammar (also included).

Let’s briefly look into every mentioned block and then finish with this impermissibly vast article:

Global Variables

As it was said before, there’s only four of them:

input– contains the string that was passed to aparse()function, so here it stays undefined and just provides global access to it, but surely it’s initialized with new value on every call toparse();pos– current parsing position in theinputstring, it resets to 0 on everyparse()call and keeps unevenly increasing until reaches the length of currentinputminus one, except the cases when any of fall-back operators were met (likechoiceorandorpreorxpreor …), then it moves back a bit or stays at one place for some time, but still returns to increasing way just after that;p_pos(notice the underscore) – previous parsing position, a position ininputstring where parser resided just before the execution of current operator. So for matching operators (match,ref,some,any, …), a string chunk betweeninput[p_pos]andinput[pos]is always a matched part of an input.options– options passed toparse()function;

User Code

What is the user code, you ask? The user code is every piece of Javascript code user may specify in his grammar, collected in one place. Think of grammar prelude, action, pre and xpre operators. The complex problem here is that user should be able to access the results of labeled operators in current scope and only in current scope, and these labeled results should be converted to variables under the very same name. So:

1 2 3 4 5 | some_rule = a:'a' x:(z:'z' { return func_az(a, z); })

(b:'b' c:'c' { return func_axbc(a, x, b, c); })

(d:'d' (e:'e' { return func_axde(a, x, d, e); })

f:'f' { return func_axdf(a, x, d, f); })

g:'g' { return func_axg(a, x, g); }

|

in this rule user code for every action should “see” only the variables mentioned in function title (so func_az should only see labeled results a and z, and so on) and of course they should contain a proper result. In other words, every brackets pair creates a deeper level of context which “sees” all the values in contexts from the levels above, and two contexts on the same level can’t see each other, since they can not intersect. Plus, the code may “see” only the labels on the left, in its context, on the same level and above, since they are already calculated, since parser goes through rule from left to right.

JavaScript is actually not very friendly to perversions like named parameters (Python, you are cool!), and, for the non-expandable parser code, like the one we describe in the article. We need to store the values and later pass them under required names to the wrapper of user code, but we can’t predict their names until we start parsing. But we want to isolate user code in functions aside from parser code, so everything private will not be visible to user not bacause of underscores, but thankfully to closures. Named parameters seem the only way to provide user with this functionality from the first sight.

Same for the second sight, though. Same for the third.

Still seems the only way. Or we’d should pass an object to every code block and ask user to refer to them as some_obj.a, some_obj.z etc., which is ugly and dishonest. May be we should drop this idea?

But JS actually hides inside another ability we may use for the good – prototypes. This one is helpful to easily go up and down through user contexts. When user JS function is called, some object will already contain all current-level values, and hold the parent-context values in prototypes chain. When we go out of a nested context, we drop the last created object and switch to a parent prototype to be a current context object.

So labels problem was solved another way, I decided to do the very same prototype travelling during conversion of a grammar to AST tree. And then I know which labels should be visible to user, I inject them directly into user function calls as properties of an object which holds current parsing-time context under known labels.

Woof, seems we got it not so briefly here. But anyway this will help to explain some things below and you’re stll with me, so I’ll try to demonstrate it with an excerpt from Gist with parser example mentioned above:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 | // This code encloses all of the user blocks (initializer and/or

// actions) in their own sandbox, so if there is an initializer,

// its inner variables will [only] be accessible to actions.

// This, however, requires an initializer not to have any

// first-level return statements (which has no sense, in its

// turn). Also, this approach keeps parser inner variables

// safe from user access, except the ones defined above.

var __user_blocks = (function() {

// functions accessible only to user code

function offset() { return p_pos; };

function text() { return input.substring(p_pos, pos); };

/* ########### USER CODE ########### */

/* ----------- INITIALIZER ----------- */

var user_var = 0;

/* ----------- BLOCKS ----------- */

// Blocks are grouped by rule name and id;

// they all get access to current context through `ctx`

// variable which they expand into their arguments.

// Arguments' names are pre-calculated during

// parser generation process.

return {

"additive": [

function($ctx) {

// additive[0]

return (function(left,right) {

return left + right;

})($ctx.left,$ctx.right);

}

],

"multiplicative": [

function($ctx) {

// multiplicative[0]

return (function(left,right) {

return left * right;

})($ctx.left,$ctx.right);

}

],

"primary": [

function($ctx) {

// primary[0]

return (function(additive) {

return additive;

})($ctx.additive);

}

],

"integer": [

function($ctx) {

// integer[0]

return (function(digits) {

return parseInt(digits, 10);

})($ctx.digits);

}

]

};

} })();

// ...

// this expression is evaluated before every parsing cycle

var $f = __user_blocks();

|

All user code blocks are grouped by rule name, so each rule has it’s own array. We already traveled the grammar AST here, when we generated this parsing code, so we knew all the labels names and injected them to proper places. When user parses some input, we know an index of user block to call, so we pass current context to a function and call it, i.e. __user_blocks.additive[0](cctx) (cctx variable holds current context).

Parser Closure

It just isolates parser code from user code. That’s it. Let’s move deeper.

Rules

Every rule from grammar is encoded using operators (that stuff described in previous part), so this:

1 2 3 4 5 | ... other rules ...

additive

= left:multiplicative "+" right:additive { return left + right; }

/ multiplicative

... some more rules ...

|

becomes this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 | var rules = {}; (function() {

// ... other rules here ...

rules.additive = function() {

var _code = $f.additive;

return (

choice(

action(

seqnc(

label("left",

ref(rules.multiplicative)

),

match("+"),

label("right",

ref(rules.additive)

)

),

_code[0])

/*{ return left + right; }*/,

ref(rules.multiplicative)

)

());

}

// ... some more rules ...

})();

|

$f is given a value of __user_blocks() on every call to parse() function.

Operators

All the operators were covered in details above, even with code examples, so for now you only should know that exceptionally the operators actually mentioned in rules are included here.

Ok, there’s one more subtlety I need to tell you about. May be you recall I mentioned that operators are postponed functions. So every operator here is wrapped so that it’s first call only stores arguments passed and second call actually performs the function code with the stored data. This may be done in different ways, like using Function.bind, for example. You may take a look at the Gist code to see which way it’s implemented in my case, but the way actually has no matter here, only the result matters. This, however is the clockwork which makes everything tick in functional way.

cc() and ref() functions mentioned in Operators chapter are also defined here.

Internal Parser Variables

Parser needs to store some private things, of course. Each of this variables below resets to initial state at the start of each parsing cycle.

cacheobject stores the rules results by position in theinputstring, so in cases of backtracking there will be no special need in recalculating. Every rule wrapped the way it checks the cache before execution and if position matches, returns the result from cache. Caching may be disabled on parser generation;ctxvariable holds the vey root of context, the topmost level of it (see above in User Code section regarding prototype chains for context levels);cctxpoints to current context level;ctxlholds current context level index, the deeper the level, the higher index is stored here;currentis the name of the rule in process of execution;aliasis the alias (seeas()operator) of current rule, if it is defined;ilenis the length of an input;

Context Management Functions

Actually, everything about context structure was described in User Code section. I’ll just remind you that new, deeper, context levels are just new JS objects which hold pointer to previous (higher) level of context in their prototype. And yeah, context is where labeled results are stored for action, pre and xpre operators, which may contain JS code intended to have access to these labels. Deeper level of context is marked in grammar with parentheses.

ctx_level(parent)creates a deeper level of context below aparentand returns it;din()movescctx(current context level) pointer to a deeper level, parallelly with creating it if requred;dout()movescctx(current context level) pointer to a higher level;inctx(f)goes a level deeper, performs the passed functionfand then immediately goes out;

parse() Function

It is the function called with evey new input to parse. It resets all the variables to their default values, clears the cache and does $f = __user_blocks() (see User Code section), for example, then searches for the starting rule and executes it in a try-catch block. If MatchFailed exception was fired during the execution, it collects all the necessary information about the failure and fires it further to user (since it reached the top level and wasn’t suppressed, for suppressed exceptions no information that should have belonged to user is collected).

MatchFailed, SyntaxError, Error Handling

Errors handing mechanics are driven by Exceptions in Pegjs-fn. safe() function suppresses exceptions fired from operators called inside it, but stores them anyway, to allow parser find the last one happened in special cases.

Some variables are used to manage error data:

failuresobject to store all the failures found, suppressed or not, gruped by postion ininputstring;rmfposstores the position of the right-most failure;nrturns the failure reporting mechanics off (sometimessafefunction is not enough to have);

MatchError is fired when parser found any mismatch between grammar and input, it stores what actually failed, the expected chunk and found chunk (or a marker, see just below), failure position as offset and two-dimensional position (line and column number) in inputstring (which may have line breaks and it’s not a problem for a parser).

SyntaxError is fired when grammar used to generate the parser contained some unexpected error, i.e. if it had no start rule clearly known.

Markers

There are few special cases, when MatchFailed exception may contain marker instead of string chunk:

EOI, end-of-input, if the final character ofinputstring was unawarely reached during parsing;SOMETHING, if it wasn’t concretely known what to expect, but there required to be something instead of end-of-input, for example.actionoperator uses this marker to describe what was expected if the user JS code informed that rule failed (returnedfalse);NOTHING, is a markeractionoperator uses to describe what was found whenSOMETHINGwas expected. Sad story;

Parser Closure Call

This call builds the Parser instance and returns it to a user. Parser instance has:

toSource()function which returns it’s own code as a string;MatchFailedexception description;SyntaxErrorexception description;parse(input[, options])function, the one that user may use to triggers the parsing process on the giveninput;

Conclusion

I hope you found this article interesting and discovered a new approach to parser generation. And thank you for being patient and reaching the very end.

P.S. Parsing this article with non-legal parsers or parsers built on a base of non-legal grammars is strictly forbidden.