Seems I haven’t posted anything for a while, since Sep 2014 to be precise—even though I had nice topics to discuss. So here’s a new try to get back to you with writing nerdy texts. Especially, considering the fact it gets more popular and fancy every day.

A quintessence of this post (not to say TL;DR):

There exists a language Elm. Which could be a new nice replacement for JavaScript. [“That’s a rough and controversial statement!”, you would say. You have a right to say so!]. And, as it happens with every new language, step-by-step, it gets its plugins developed for every modern code editor / IDE. Every such plugin is usually written by the new-language community rather than developers of this particular editor / IDE.

Kind of a problem for the developers of these plugins, is the fact that for the moment Elm has no reflection (a way to get a type of an entity) and tends not to have it at all. By itself, having no reflection is rather a good thing, usually it complicates the language syntax and/or libraries a lot. But the detailed types information is needed to implement helpful things in editors—nice type hints, nice auto-completion etc.

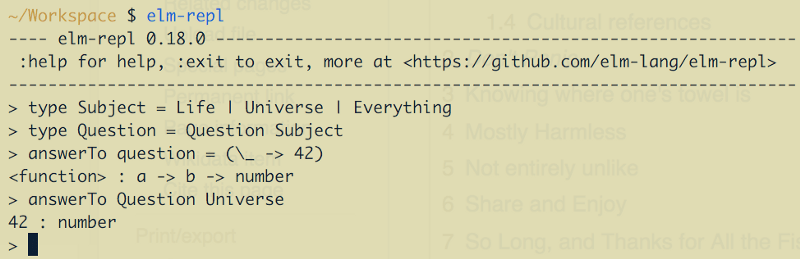

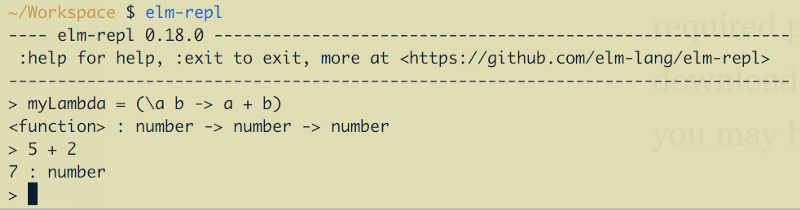

It could look like nothing special from the first sight—a bunch of languages have no reflection, so usually people write IDE-dependent Lexers and Parsers or use some other ways to get type information. But with Elm, there’s one subtle difference: it has a REPL which shows the correct type of an entity (variable or function) for every entry. It works not with the help of language, but with some hidden tricky features of the compiler (I will cover them later). So why not use the official REPL result to get this useful information?.. The post answers why.

Also, this post shamelessly promotes the node.js library named node-elm-repl, to those who develop Elm plugins for IDEs, but only for those who do not disdain running node.js processes inside their target IDE.

So, if you are not interested in Elm or writing plugins for IDEs or parsing binary files, the article could not be interesting for you… Or actually it could?

Disclaimer: (I always have disclaimers in my posts. Why ruin the tradition then?) Every conclusion below is a subjects to discussion, since what’s happening here is just an investigation driven by a single human mind, usually tending to be so offensively wrong, that only dozens of years prove how was it surprisingly right from the very beginning;

Why getting types in Elm is important at all?

Some may be satisfied with Lighttable way of determining the type — selecting the expression and pressing a special key to get the value and type from the execution in background REPL process.

Lighttable was probably the first IDE inspired by Bret Victor lectures on sandboxing and gave us some ideas on how it would work in real life. For now, there are much more implementations of sandbox-driven programming, and some of them actually show the results live.

There are Swift Playgrounds in XCode, there is Haskell for Mac, there is Jupyter (formerly iPython) Notebook, there are DevCards in ClojureScript, there are React Storybooks, there is Wolfram Alpha and new Wolfram Language, and there’s datalore.io from JetBrains—all of them have something different, some are visual REPLs, others are livecoding environments, but in general the concept is in observing the results and/or statistics of the code expressions on the fly and usually side-to-side.

Several of the listed environments provide users with the way to change the input values using special controls without modifying an actual code — to let users supervise how subtle changes could affect the output.

Haskell for Mac is probably the closest thing to what would be cool to have for Elm. (Especially, considering the fact that Elm has quite stable WebGL package already, it could be huge).

Why would it be cool for Elm in particular?

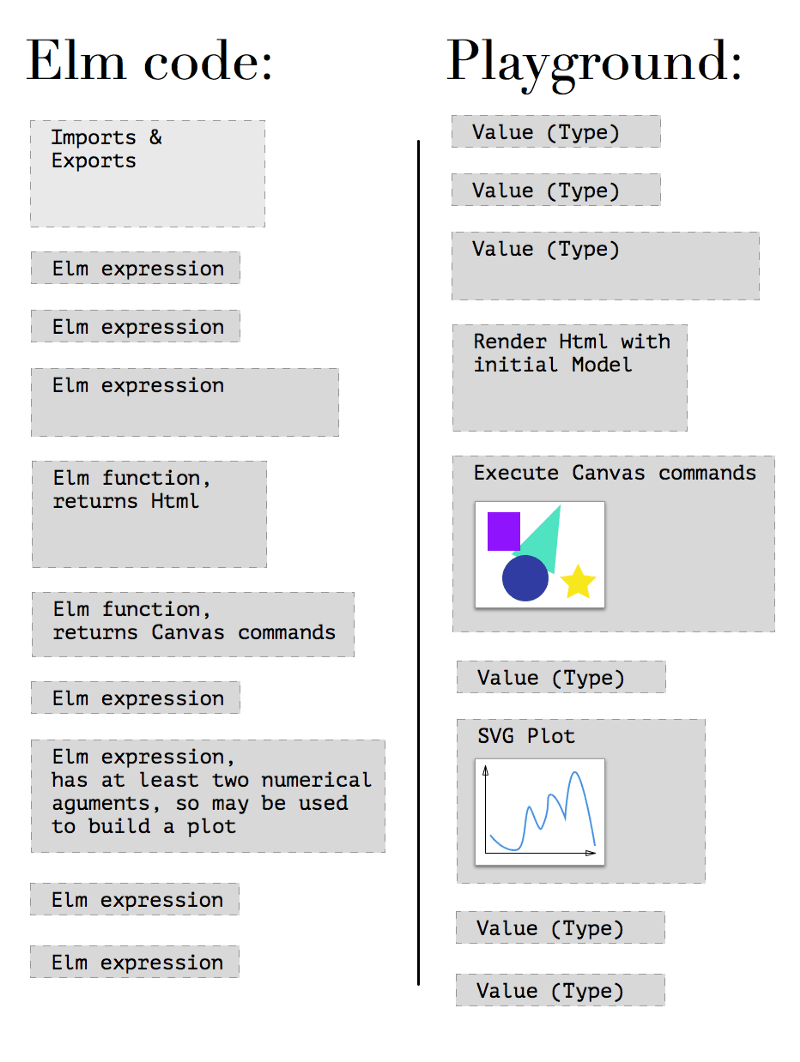

First, unlike Python and JS, Elm is strictly-typed language, so actually any variable has 100% guarantee to be a number, string, HTML block, canvas or some user-defined custom type, including optionals, and this variable is guaranteed to stay this way forever, starting from the moment it was defined somewhere in the code.

Second, as in React, Elm could treat functions, which return some markup (i.e. HTML) in response to changes in a State, as Components. So, if your expression returns HTML (or SVG or commands for canvas context, or whatever you could treat visual) and your IDE supports sandboxing, you may observe the changes to your Components just when you change the State bound to this Component. Following The Elm Architecture, views are the functions which return Html in response to any change in a Model.

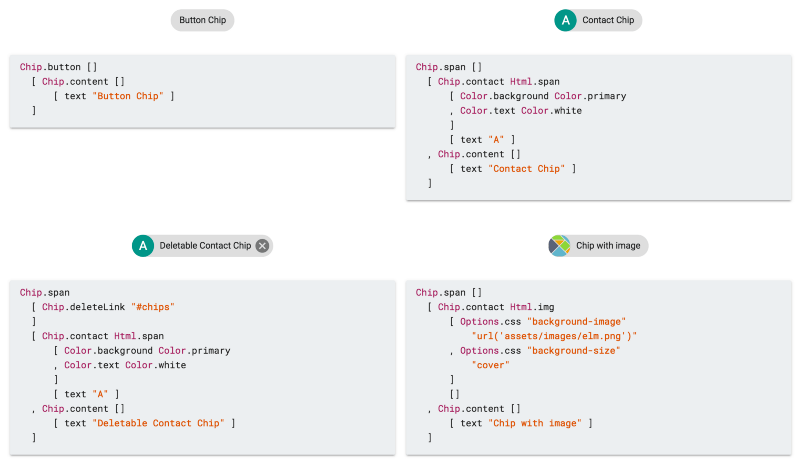

(Above is the example of Elm Components provided by elm-mdl library.)

Third, what is even better for Elm, all the expressions are functions and any function could be called with omitting some of its arguments (we name it „partial application“ in functional programming). This allows the said plugin to substitute some arguments with suggested values and draw a plot of all the possible results, for example.

Oh, and the main point—this is the thing what Evan dreamt of when presented the debugger :).

So, Elm is the language which fits sandboxing in its best.

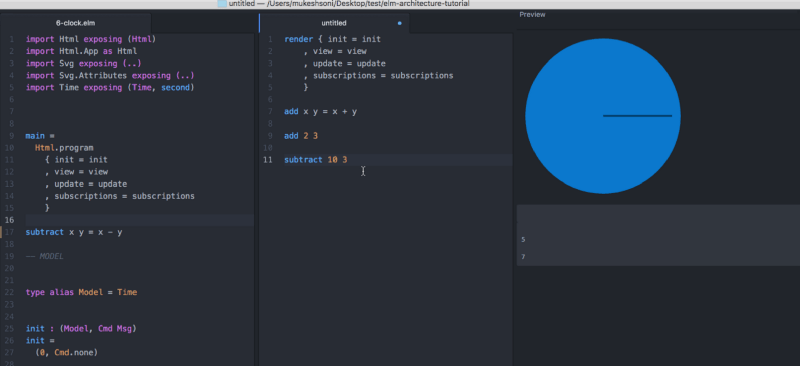

Mukesh Soni is developing a plugin for Atom which brings React Storybooks-inspired interface to Elm.

But user needs to wrap blocks of code in a special form and to write things-to-try in a Playground panel, unlike Sandboxes which provide programmer with the view and control over the actual code being developed.

The idea of binary-parsing .elmi actually started from the moment when I connected with Mukesh (he had the plugin working already) and decided to try to implement things by detecting the types. He completely agreed that would help, so I rushed into binary investigation and Mukesh helped me a lot in my findings. Unfortunately, for the moment the integration of a working type-detection into the plugin itself is in a frozen state due to different reasons. And especially, due to my current occupation (JetBrains, in case you wondered) it seems better to use this skills/code to improve IDEA plugin instead :). Though anyway, that would be cool to have it everywhere. That’s one of the reasons why I write this article.

Some links to Google Groups discussions, to provide you with the progress of getting types from outside with the language itself or its utilities:

- 2013. Evan tells he is working on providing types, probably using

elmifiles (these experiments were abandoned later); - 2013. The discussion on the ways to organise the binary files;

- 2016. The discussion on AST Tooling, p.1;

- 2016. The discussion on AST Tooling, p.2;

- 2017. The discussion on pairing Elm with MS Language Server;

So it is important to notice, that things could change drastically in Elm 0.19 or a bit later and may be at some recent point we’ll have the types with a call to compiler in some way, or have a MS Language Protocol implemented. I really have considered this twist of faith, and I think this could lead to a better Elm-IDE world without binary parsing and that’s what we all actually need. Also, elmi file format could change in any way Evan wants. Yet I have awesome tests. If that will happen soon, this story has completely no practical point, and rather could be an interesting, but pointless stack of information. Please consider that before reading further.

What Elm IDE Plugins use for type suggestions right now?

(There could be errors in this list, please correct me if something is wrong or outdated)

- LightTable Elm Plugin: used elm-oracle before, now directly uses elm-repl to evaluate code in-place, and its own peg.js-generated parser to extract types. In terms of getting types and values, both work with limitations and have time issues, at least afaik;

- IntelliJ IDEA Elm Plugin: parses types with its own parser;

- elm-oracle is a JS tool to extract types from Elm documentation existing online: requires internet connection;

- elmjutsu, a recent development, a toolbox for developing Elm plugins in Atom: no requirement of elm-oracle, still parses the Elm Documentation, however it stores type tokens in a local cache, so usually works quite fast and constant internet connection is not required;

- Atom Elm Plugin: uses elm-oracle;

- VSCode Elm Plugin: uses elm-oracle;

So, the solution is either writing a full custom Elm syntax parser or parsing documentation, for now. Regarding first option: custom syntax parser is also required to parse imported packages code to get types for them. Second option is used mostly by JS-driven tools, not to parse the code of requirements as a time-wasting issue. To get the type when it’s not specified, Elm allows it, programmers use elm-repl. But the Elm compiler itself already has this information at hand when it compiles the source!

How could it be improved?

No requirement for internet connection is still better than having it. In some countries it is still slow, in some countries some sites are still restricted to be visited. And programmers do want to work in trains, buses, underground… A lot of areas are still not covered with connection or you have to pay for it and/or you have to authorise even when you don’t want to—a lot of barriers now exist (and there were even less before), especially for travellers.

Evan, the author of Elm language, however, had noticed once, that at some points documentation could be stored in a package distribution itself.

In case of using REPL, the connection is only required if you have no required package installed (“I haven’t found your package locally, may I download your package?”, it asks, and you may agree). In all the other cases you may happily continue asking it for types:

Except the fact that every request for a command is really slow. As a user, you may not notice that at all, but it takes 300ms to several seconds for every request even on my modern machine. If you wrap the call with node.js using child processes, and it turns out you need to run an isolated REPL process to detect the type of a single expression, so the pause between single calls becomes completely unpredictable.

Why node.js? Most of the popular editors nowadays are either powered with JS, or may run JS from the inside. Plus, Elm compiles to JS for the moment, plus you may use native JS modules to connect JS and Elm, plus there are JS-ports for data communication with JS—so JS is like a really friendly neighbour. At least for now. While we are yet not into WebAssembly.

Another problem: if you want to extract the type from REPL this way, you need to parse it from the output. It’s not the same as writing the language syntax parser, it’s not that hard, but with a subtle change in a REPL output format (which could not be included in What’s New sections), your tool breaks. If some weird OS breaks the output, you tool also breaks. And this format is not bound to a compiler version, actually it’s the same as for documentation the plugins parse. No guarantees at all. And anyway, REPL itself is rather an intermediary in terms of getting the type.

Digging into the REPL logic

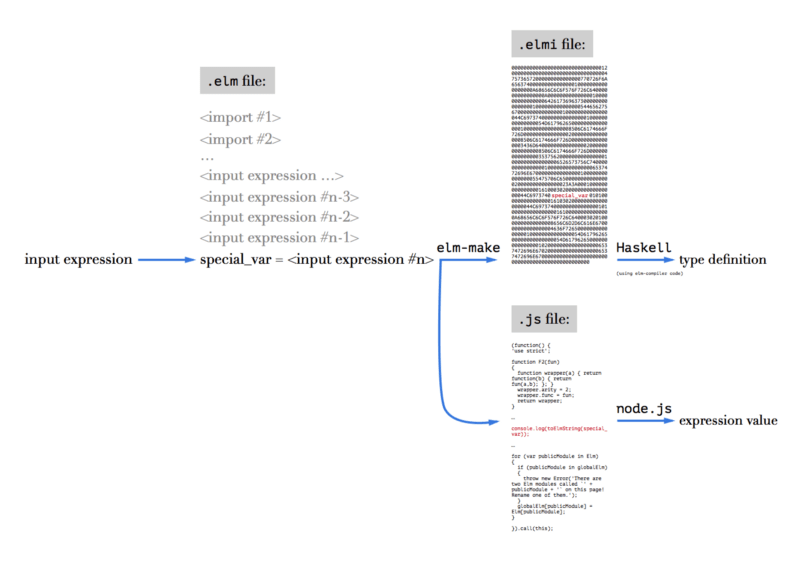

But if you dig a little into the Elm REPL code, you’ll find that Elm compiler actually creates one magic binary file to store the types. Not in the directory with the code, but in elm-packages directory and below. This file has .elmi extension. And REPL uses it to get those types, surprisingly, in a quite dirty way:

- Take new input expression, there should be the only one;

- Append it to all the imports of the expressions executed before, so imports will go first and will be shared with previous expressions;

- Assign your expression to an exclusively-named variable (easter-egg from Evan here, but I won’t spoil it);

- Concat the lines, put everything in a temporary

.elmfile; - Compile this file with

elm-make; - Go into

elm-stuff/build-artifacts/user/project/1.0.0and find the corresponding.elmifile there (which is binary!); - Parse this file with the same Haskell code which compiled it into binary code, and so extract the variable type from it;

- Also, take the value of this expression by executing compiled

.jsfile, including some additions to log the evaluated value, with node.js; - Delete everything temporary, like it never happened (

.elmifiles stay for reuse, to the moment source was changed);

This is what I was able to get from Haskell code of the REPL, along with using some UNIX utilities to lock files lying in a known directory from deleting—so I was able to patiently analyse them with no rush.

Trickity-trick #1: Hello, my dear young shiny developer! This is the first exercise of mine for you. If you have already read some fairy-tales about the UNIX shell, could you please solve a minor problem for me? The question is: how would you prevent the file from deletion even before it’s being created and without knowing it’s name? …

Getting rid of intermediaries

Now, when the algorithm is known, we may drop some actions we don’t need or make them optional. Since the requirement for me was JS/node.js usage, I decided that it’s ok to drop Haskell part and make everything JS-driven.

Which means, we need to parse the binary .elmi file with server-side JavaScript!

Actually starting to parse

There are a lot of binary parsers for node.js—however, it turned out, that not every parser supports everything expected—reality bites. Some parsers fail to do nesting (and .elmi files do contain nesting, since type definitions may recursively refer to themselves), some are abandoned, some require special parser syntax (like LEG/PEG etc.) and so they use a lot of time to convert this syntax to JS-friendly AST (to say truth, with these parser generators you often may pre-compile a JS parser to a reusable JS file, but usually this file takes a lot of space).

I decided that having JS chain-like syntax is enough for that purpose — to simultaneously be able to feel the flow of the parser just from the syntax and not to waste user resources. Through some exploration, I chose two ones using a list of these strict requirements:

- node-binary from substack: it has nice syntax, and is minimal;

- binary-parser from keichi: nice syntax and also minimal, has nesting;

First, I thought I may just use .tap() function of node-binary to dive into complex structures, but it turned out I also was required to have a .choice() function to decide which sub-parser to call if some byte equals some expected value, and also the binary-parser from keichi seemed to be not so abandoned (2012 vs 2016).

Yet it required some modifications, though.

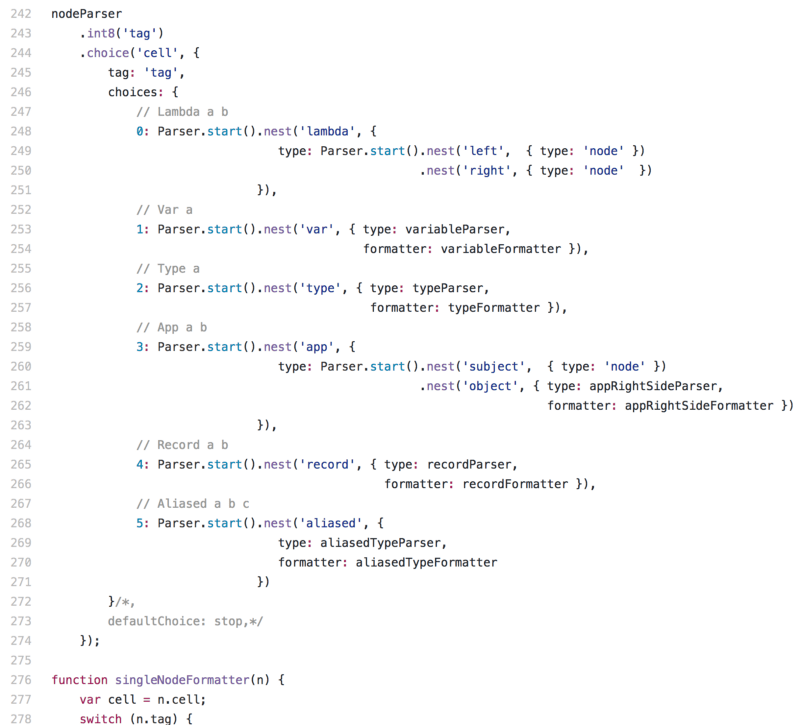

First, I was required to implement support for named sub-parsers (they could be defined as functions) to be able to reuse them without re-instantiating, and so do a real recursion, using sub-parsers as cells.

Second, it uses eval-like way to call user-defined callbacks in a required context (actually, it was new Function constructor, which is treated unsafe and leads to eval call in the end) and Atom infrastructure was not very fond of it, so I was required to add loophole package to the package.json with some monkey-patching, to make this code safe (code made safe with monkey-patching, sounds really weird…).

Both Pull Requests are not merged into the original repository of keichi yet.

The code: Here’s the code of the final version of the parser, written with the help of my own modification of the binary-parser package.

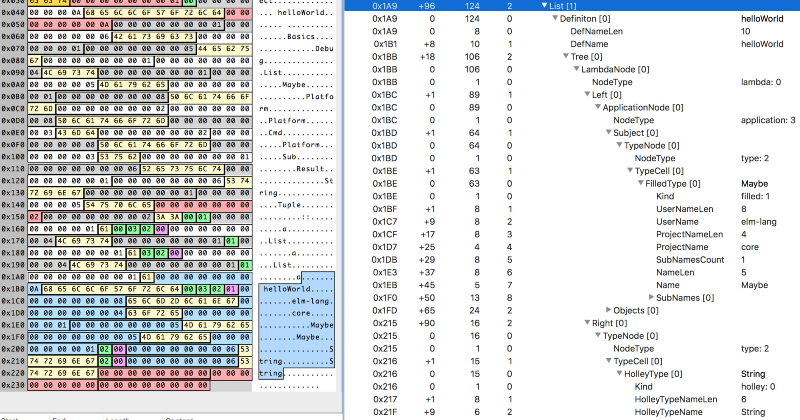

Diving into the binary

As a source material of .elmi files and as a goal to parse properly, I decided to use my implementation of exercises from Exercism.io. They have divergent but simple combinations of types, which I used to actually test the code (chai and mocha to the help, nyan!). By locking the files created by REPL, I was able to see which way the REPL extracts the type of variable (by creating a temporary-created variable and a file for every new expression, as it is described above) and then get binary results.

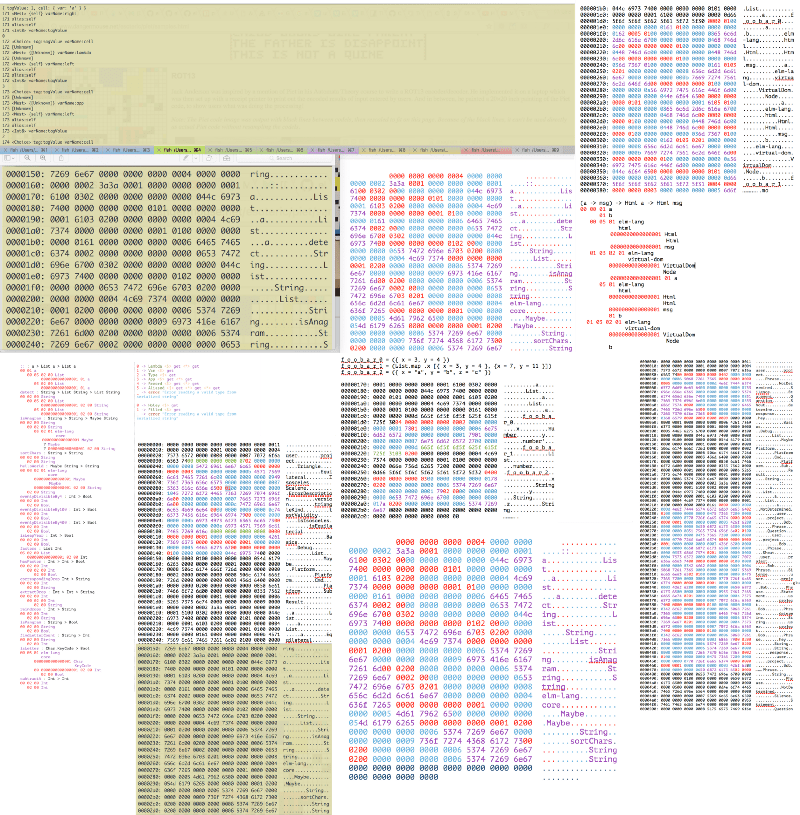

First (actually, in process of writing 80% of current parser code), it was a manual trial and error: using shell binary viewer and passing the result to MacOS Pages (ha-ha!), I changed the font to monospaced, marked the areas, appearing to be common, with different colours and tried to find a structure and relations between them:

Trickity-trick #2: Which UNIX tool you, the almighty UNIX master, would use to see binary file contents in a beautiful and friendly way?

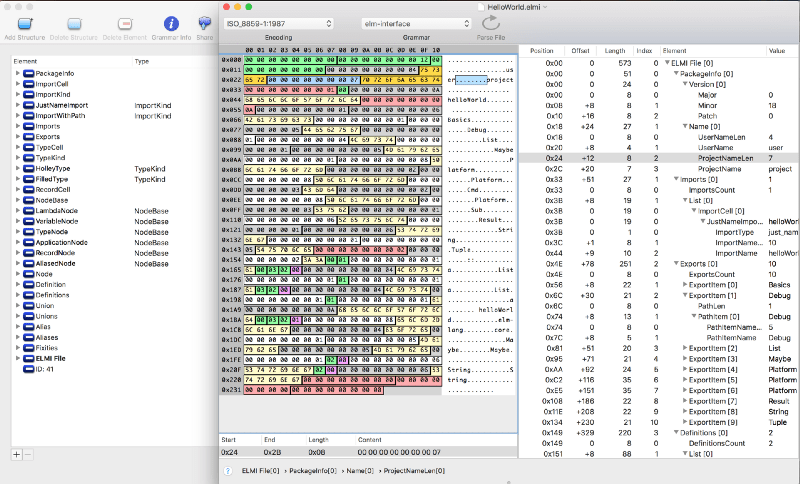

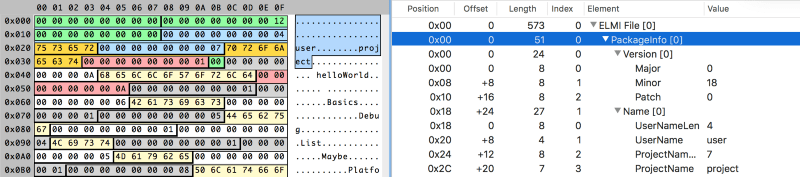

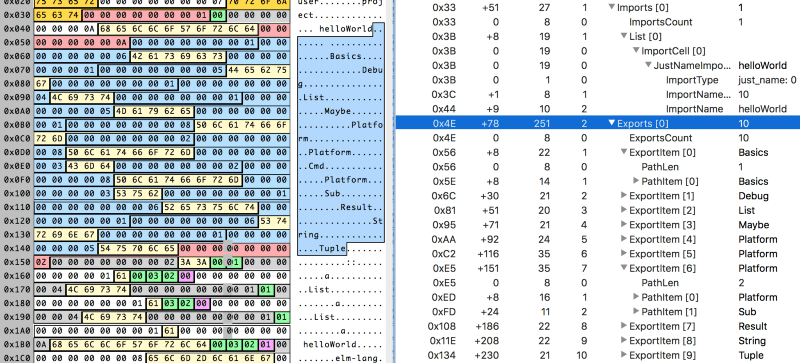

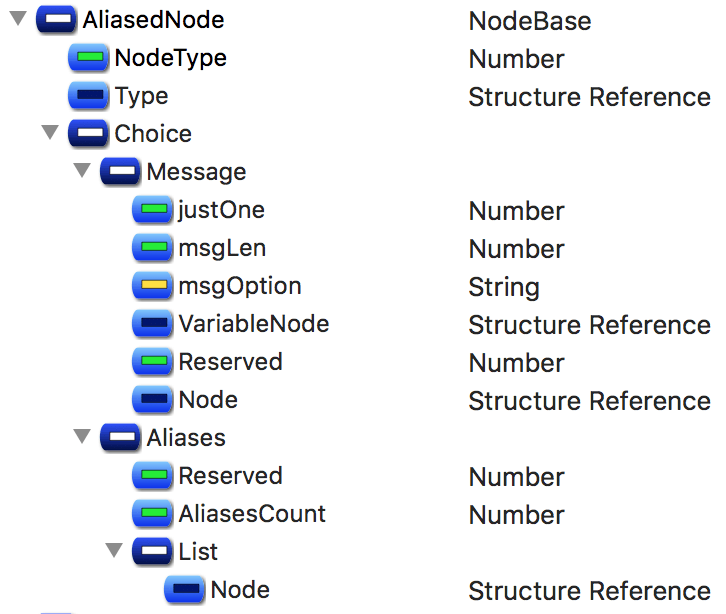

Then, closer to the finish, I discovered a very nice tool named “Synalize it!” (formerly Hexinator). Basically, this tool is the very binary-reverse-engineer friend.

It allows you to open binary file, see all its bits in a nice grid, easily mark regions with a mouse, and assign name/colour pairs to these regions, defying how many bits they take in a file. After that, you may reuse the pairs to mark similar regions with a single name/colour. Apart from that, this tool has it’s own XML-based .grammar definition format, which supports different ways of nesting and reusing already defined structures. And yes, this tool costs a bit, if that’s a downside to you.

The .grammar file for .elmi also lies in the repository.

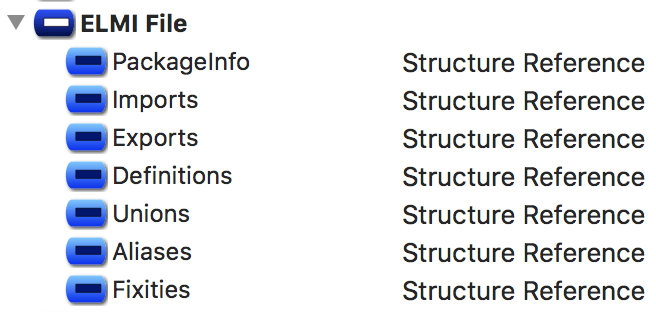

Destructuring ELMI in details

Some primitive conclusions were quite easy to determine from the start:

- strings are defined with 8 bytes of length and the contents follow this byte;

- first, there goes Elm version and package name;

- then, there go imports, prefixed with a number of them used;

- then, there go exports, prefixed with a number of them used;

- then, there go type definitions paired with variable names;

- this usually ends the important part of a file (sometimes not);

Some things were much harder to evaluate: for example complex structures, when stored in binary, usually consist of several marker bit-cells with numbers, following the marker bit-cells with the same numbers, but in this case these same numbers could have totally different meaning, and in theory could (or could not) define the number of bytes we should read after reading such marker, but these bytes, which we should probably read, could also include markers with different meaning, and also some markers inside them could define that the structure should split in three branches from now on, and each of these branches starts with some markers… truly, when you destructure these plain sequences of senseless numbers and try to form a meaningful stable tree from them, it feels like you are some kind of holistic detective…

How a line of random byte and string sequences could lead to a meaningful structure with cells and markers.

Especially when you do it in Pages App. So, at least don’t do this kind of stuff in Pages App unless you really want to get weird.

The project has all the tests required for every discovered example of complex type, including pre-compiled .elmi files and not-yet-compiled .elm files to test.

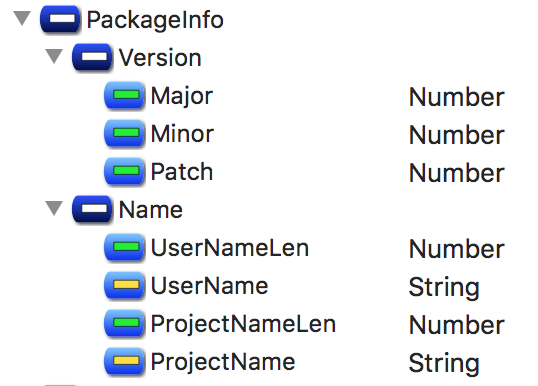

Package Info. Package info requires no comments, it just contains the Elm compiler version, package author username and project name.

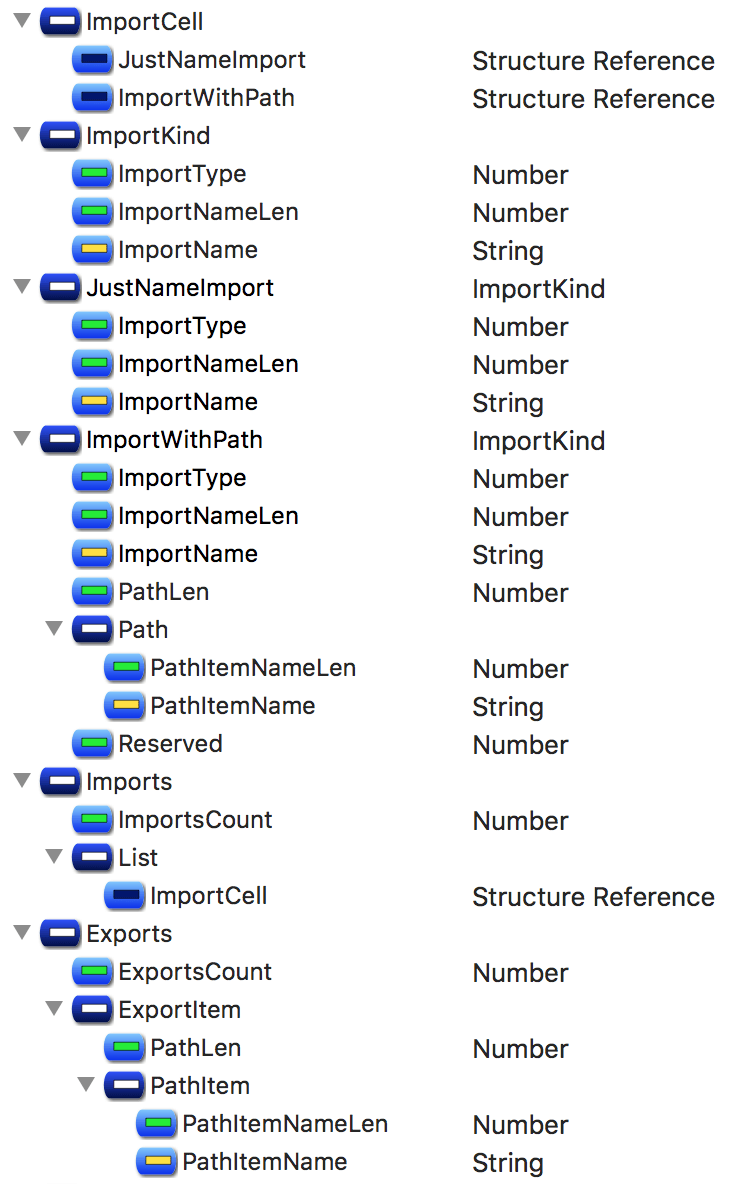

Imports. Any import could be an internal packages and so defined just by name (marker 0001), or require a full path to a package and type (marker 02).

Exports. They are just paths — string arrays of different lengths.

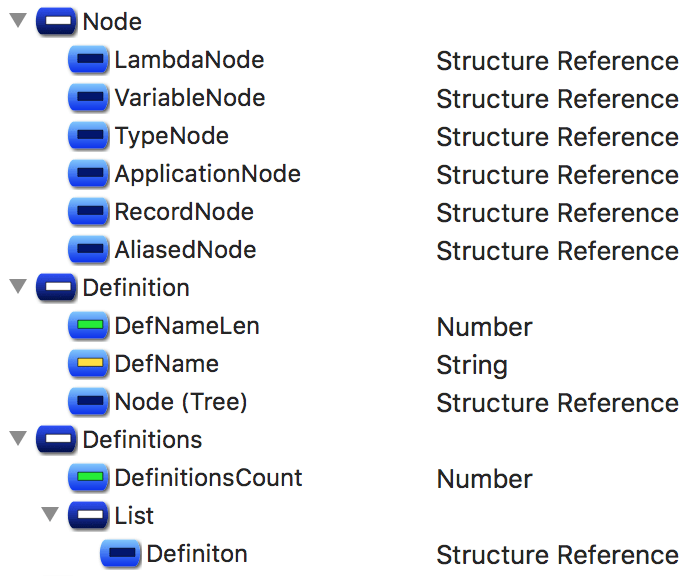

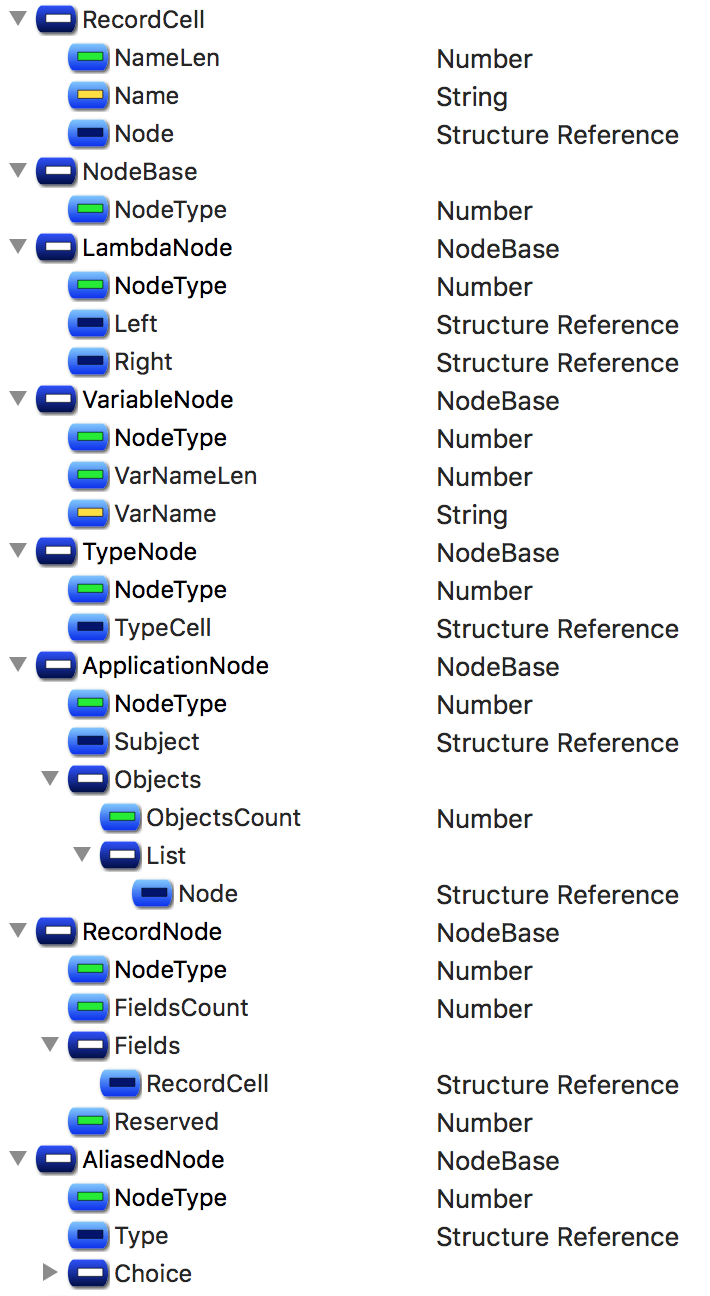

Type Definitions. Type Definitions are the most complex and complicated things in a file. They are the ones who contain mysterious markers-inside-markers constructions described above. But I’m here to help.

The kinds of structures here are a bit different to actual Elm types but still they define them in a deterministic way. The single type is defined with a recursive structure of data cells, where a cell could be a:

- Variable (marker is

1): just a reference to some existing variable by its name; - Lambda (marker is

0): define something that applies left side to the right side—in Elm code we represent it with an arrow (→) when we define types, i.e.String -> Int, whereStringis on the left side andIntis on the right side; - enclose either Holley or Filled Type (marker is

2): this cell could be defined inside any other cell, where Holley means the type defined in a local scope and thus referred by a single name and Filled means the type which is defined not only by name, but also by user, package and module name; - Application (marker is

3): define something that has a subject and an object—in Elm code we represent it with a space () when we define types, i.e.List Int, whereListis the subject andIntis the object; an infinite number of objects could be applied to a single subjects; - Record (marker is

4): a record with named field↔type pairs inside it, prefixed with the number of stored fields inside; - Alias (marker is

5): an inferred type which has a reusable alias inside the type definition—think ofainHtml a,msginCmd msg,fooinfoo -> fooand so on…; or a type alias;

NB: lambda could only have two parts, so the definition like String -> Int -> Bool is stored as two lambdas, one inside another: lambda (Int -> Bool) is applied to a String type, and so the root lambda cell is (outer-lambda: String -> (inner-lambda: Int -> Bool)); Trickity-trick #3: think on how this could be connected to function definitions in Elm types;

The trick here is that almost every cell may include another cell with its own internal namespace of definitions and numbers, and this is the reason why plain structure of bytes looks so repetitive from the start. If you have Ph.D. in Binary Reverse Engineering (like I do not), you would treat that obvious, but for newbies there’s always an advice not to be fearful of the structures and believe that there is a meaningful reason behind every bit, every byte, every Life, every Universe and EveryThing…

Unions, Aliases, Fixities. Any of these seem to have no effect on type definitions, so these parts could be skipped from parsing completely.

All the schemes above, along with the .grammar file, do define the structure of any .elmi file [I found yet]. If you have found the .elmi file not satisfying to this schemes and grammar, please fork node-elm-repl repository, add this file to the specs and then make a Pull Request to the origin.

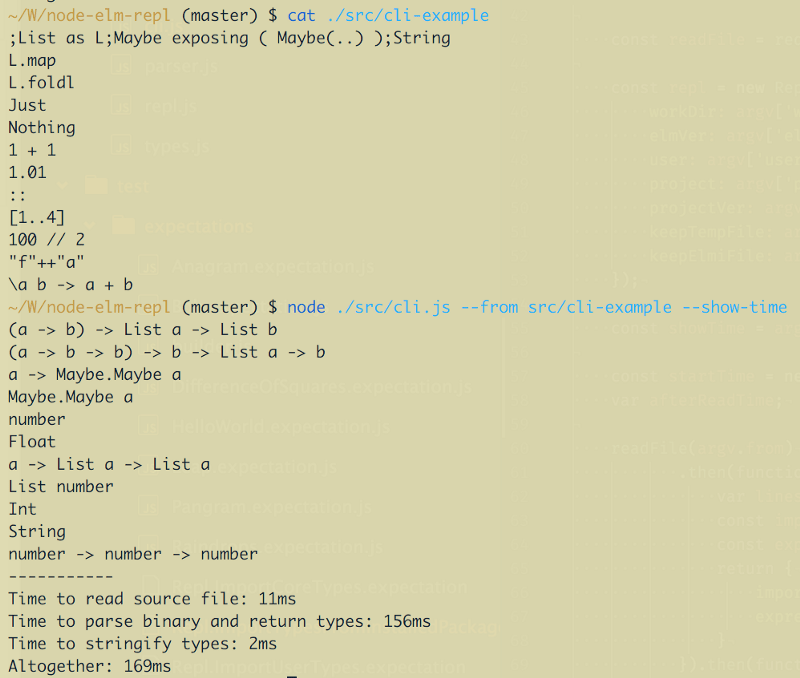

So, now we know the type (and a value) of any expression, node-elm-repl in Action.:

The Verdict

If you are an Elm plugin developer for any of the IDEs, please find any possible way to develop and integrate sandboxing with Elm in your favourite IDE, since, considering all the language features, it has all the chances just to be awesome.

If you are someone who have read this article from the beginning to the end just for fun, please keep being this kind of a person.

If you are expecting to binary-engineer a file in some nearby future and read this article just to know how its usually done, consider using Synalize it! for this case. Or else, just use hand and paper. Or Pages. Or Excel. In any way it trains your mind to solve deeply-connected things. But some tools really help not to go too crazy.

If you planned to parse the .elmi file and extract types out of it, now you have a complete technical specification… and a code in JS to do it automatically.

Solutions for the tricks

- #1: nothing special, just use

chmodandchownto set a sticky bit on a directory which could contain a file, to prevent a user who runs the application (REPL, in this case) from deleting anything inside it: http://unix.stackexchange.com/a/20106/7667; - #2: even less special, nice util named

xddis your friend: http://unix.stackexchange.com/a/282220/7667, http://stackoverflow.com/a/20305782/167262; - #3: no solution at all;